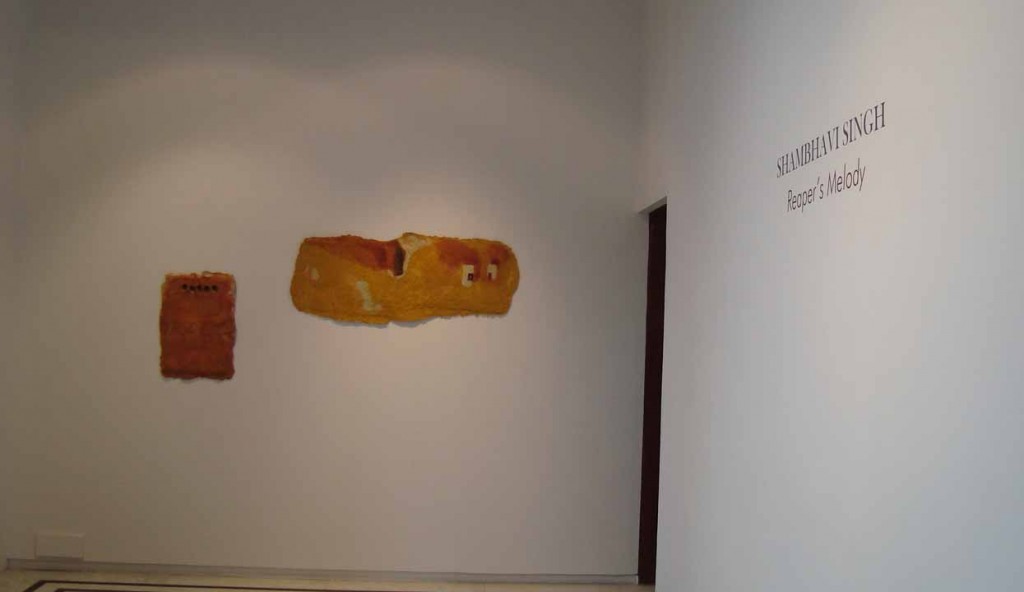

Interview with Shambhavi Singh at Talwar Gallery, New Delhi

Written by Monica Arora

Shambhavi Singh’s ongoing exhibition at the Talwar Gallery (from 6 September 2014 to 3 January 2015) was indeed a revelation for me. Having lived all my life in New Delhi, a completely urbanized cityscape, I was mesmerized by the paintings, sculptural installations and paper pulp works on display. Deploying the basic earthy tones, here was the recreation of the rural Indian landscape, in fact of not just the earth element but also of water.

At the entrance of the gallery was this huge iron installation entitled ‘Rehat’ denoting the iron rope drawn by bullocks to draw water and irrigate the fields, a common sight in almost every Indian agricultural village. Moving on, I discovered the ‘Ghar Andar Bahar’ installations created from cotton pulp and pigment reminiscent of the rough unfinished texture of small mud hutments in the villages. The sheer use of fading browns and pale yellows juxtaposed occasionally with the blackened soot of a diya placed in a tiny niche in the wall completely recreated the somber ambience and muted lighting within the walls of a struggling farmer’s humble home.

Megh Meyrd, Acrylic on canvas board ( in 14 parts), 206” x 49”, 2014, Courtesy Talwar Gallery- New York New Delhi

Considering the fact that monsoon and clouds are an integral part of a tiller’s life, Shambhavi has created this evocative series known as ‘Megh Meyrd’ depicting myriad fleeting shapes of grey clouds (known as ‘megh’) in the sky, which the farmer looks up to time and again in hope of ample rainfall for the cultivating season as less rain and drought would mean the end of his crop as would excess rain lead to flooding. These black and white creations on canvas are like a dreamy extension of endless clouds forming every other day during the monsoon months. To describe the awe-inspiring hues of mother earth in all its glory, Shambhavi uses ‘Meryd’ series, again acrylic on canvas, to portray these little meandering mud tracks, sometimes complete and sometimes akin to small pieces of a puzzle, which enamour and enthrall onlookers all at once. Similarly the ‘Kuan’ series are shaded with interesting shading and deft brush strokes whilst expressing the simplicity of rural agriculturists and at the same time the uncertainty underlying every harvest season portrayed most effectively by a deep yet nearly dried-up well.

Girvee Lal and Peela, Acrylic & oil on canvas, 72” x 108”, 2014, Courtesy Talwar Gallery – New York New Delhi

Girvee Nila, Acrylic & oil on canvas, 72” x 108”, 2014,Courtesy Talwar Gallery New YorkNew Delhi

Red Kali, Watercolour on handmade paper ( in 12 parts ) , 160” x 90”, 1998

Shambhavi’s depiction of the ‘Kaali’ as this “huge red powerful triangular fire altar” is a very powerful interpretation of the feminine shakti as perceived by the artist’s vision. And I was most deeply moved by the thumb impressions of farmers in the ‘Girvee’ (mortgage) series. The angst and anguish of the Indian farmers bent under the moneylenders’ and bank loans and the duty to feed his/her own family lead them to mortgage their land, homes, belongings and eventually even commit suicide as has been the case in so many states of India, particularly Maharashtra, Chhatisgarh, Bihar, and so on, has been conveyed with much aplomb and finesse in these three paintings. The intricacy of the fine lines of the fingerprints and the pathos generated by the symbol of the ‘angootha’ or thumb of a poor uneducated farmer conjures an image of the farmer’s plight and helplessness. Having lived in rural Bihar during her early life, Shambhavi Singh has recreated this body of work both from memory and a keen sense of observation, bringing to fore the several impediments omnipresent in lives of thousands of farmers who are responsible for feeding the country but don’t have enough to feed their hungry children. I decided to explore a bit further into the artist’s reasons for choosing the numerous symbols of rural life as the inspiration and stimulation behind her ‘Reaper’s Melody’ exhibition through an online interview. This is what she has to say:

Dear Monica,

Thanks for visiting the show. I am pleased to have received your questions which reveal so much of your appreciation and insight into the Reaper’s Melody . I am happy to answer them here and also look forward to seeing you whenever you find a time convenient to you. Thanks. Shambhavi.

Narrate your early childhood experience(s) that most influenced you and inspired you as an individual and an artist.

Like most of us of my generation, whose family still had homes and cultivation in villages, I would be sent to my grandmother’s land during long vacations from Patna. Even as a kid I could vividly see the fragile and rather tough existence of the farmer from very close quarters. The landowner and the tiller, both were caught up by nature’s cycle, sometimes brutally cruel, often heavenly and munificent. Floods, droughts, heat, inclemental rain and darkness were all a bouquet served by mother earth to the farmer, loyal, expectant and hopeful. Nothing was wasted in a time which held creation and life sacred. I could see that the farmer’s being was essentially conjoined in sympathy of us all. Frugal, magnificent, monumental. Round the year. Each moment alive and felt. Her instruments were simple and did not invade earth’s consciousness, did not trifle with it. She would only take out what was essential for her family’s existence. The rest was devoted to us, shared, with the larger fraternity. Even now this is the theme of her life. It is just us, or what we have become that has led to a huge chasm between us, her and mother earth.

Which are the myriad mediums that you dabble in and which one do you find most effective?

There is a very organic link between the farmer, her implements within her home and on the field. All is connected. All gets used. Bamboo, rope, metal, trees, plants, leaf, man and animals. Like them I also use all and any media that inform my practice and take it forward. Clay, cotton pulp, natural dyes and colour pigment, charcoal, iron, brass and graphite, they have all been used in my work ever since i started my life as a thinking artist who breathes through her art. Many people have noticed that while I keep expanding my training in painting, all my work are in the nature of a constant narrative that evoke installations. You would see that in Reaper’s Melody too. All the work are inter-connected and guided by an essential motive. I work with the farmer and like her. Always.

What is the story behind the Rehat installation depicting the strong iron rope around the wheel used to draw water from a well, omnipresent in almost every village of India? It is such an evocative piece of art beside your Red Kaali and Girvee Neela. Kindly tell us how and why you chose to paint them in a most unusual manner and yet so effective that they evoke a range of emotions in the onlooker.

In modern times, we keep evoking that which is lost to us. That which sustained us in the most basic, organic way. It was both progressive and sustainable. With ‘development’ came oversized populations, thoughtless, meaningless growth, unimaginable pressures on land and on earth. Exploitation became the buzz word in which humanity became the arbiter of all. Rehat is a reality from an earlier age. Rehats were everywhere. Feeding water to millions of acres of farms. Of my home and the world. Driven by bullocks who would go round and round, around a hub on the ground. The hub geared to the axis of the water garland would make the wheel, whose spokes ended in water containers, go round and round, up and down. Up and down. Like an incandescent rhythm beating its heart to ethereal poetry. The container bowl go into the well / pond and draw the water out to fill the rivulets / canals which would spread out into the horizon to irrigate land even beyond them. A simple triumph of mechanics driven by repetitions, cycle and life. Bullocks, iron, wood, gears. Simple. Circular. In which water, darkness, light, metal, wood, man, the beast would all coalesce to create an aural and visual cohesion. Now an anachronism in midst of modern, tech-savvy times. Beating to rhythms of earth. Then fume spewing acrid diesel pumps took over. The sounds shifted. From the gentle chup-chup to the rude stacatto groans of the pump, mimicking the gun. Breaking silence. WaterGarland rekindles. the romance for the idyll, in chaotic times. My Rehat is woman’s ode to what on appearance is a masculine act turning into utterly feminine and earth like, realised in her vision.

Growing up I was always drawn to Kali as the embodiment of eternal feminine powers of creation and destruction against grave provocation. The Kali Temple on the banks of Ganga thus became the supreme junction of my awareness of growth into a woman. Two Goddesses merging into me behind a temple of learning, next to Ganga. When the time came for me to create Kali in my vision, I was seized more by the abstract reflection of Kali’s powers in all our lives rather than the animistic iconography used by Kali’s devotees everyday. My prayers to Kali did not have to see her in an anthromorphic form. Instead the triangular, rapier edged formation of her tongue, the red hot depth of the triangular fire altar within the temple and her wide open angry eyes denoting ceaseless vision all inspired me to create an abstract depiction of the angry Goddess Kali.

It was her tongue, hungry and emblazoned by crimson blood, which held centrality in my vision. Her rage screamed at me just like Kali must have screamed, first in helplessness and then each time she must have drawn her sword to cut down the asura – the evil force.

Thus the dark Goddess’es dark, black tongue held centrality in my depiction of her on my canvas. The tongue set on a dark crimson background portrayed my mental state while thinking of Kali. Her powers for anger, her capability for violence so that goodness triumphs over evil and her profound strengths guided towards annihilation. This inevitability of violence in the face of evil has always intrigued me, because it lends itself to multiple interpretations, subjective analysis and the grey areas within a sea of darkness. Somehow one has to see the light within all of it.

This work I must mention was made first in 1998 in Amsterdam and my thoughts on Red Kali are from that time of my young self growing up, within violence.

Stakes on land have got narrower in modern times. However, I am no blinker eyed inncocent who did not see the malicious influence that feudal practices had on the tiller, the worker of the land, the farmer. Most farmers work for basic substistence and do not save anything. What they grow provides them sustenance. The result is that as ‘development’ has taken over the farmer has to surrender her land. By force or by design, human not cosmic. Ignorant and often illiterate, she surrenders, mortages her land. Her thumb impression both a metaphor and actuality of the real transfer. Of land, of livelihood, of sustenance, of despair, of the ultimate migration. To raise industries and ugly urban sprawls. The three canvasses marked Girvee Neela Peela Lal, while evocative of Barnett Newman Who is afraid of Red, Blue and Yellow, brings to sorrow the stamp paper, the thumb impression and the blue ink pad that mark the surrender, the transfer. Yellow ochre is earth and red is the deadly game we the humans are playing with earth.

Considering the recent spate of suicides by Maharashtrian farmers and more elsewhere in Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Chhattisgarh all around the country, how do you think can painting bring their problems to the fore, otherwise lost amidst the other ‘more happening and breaking’ news stories?

I would not know how art and artists can influence and even positively change what seems to be an irreversible slide. If art had real powers then the slide would have been stopped by Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali and Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zameen. Half a century later we are living in even more ‘progressive’, dangerous times. A danger that surrounds us all, rich and deprived together. It is the rich who does not understand, does not share, ever. It is the rich who is ignorant, illiterate despite commandeering all our resources. Hence the suicides, hence the hovels, hence the global warming, hence despair. My art still like the eternal optimist wants to show, share light. Of the farmer and his pride. What is the option but to keep trying in the best way each of us can.

How does a day in the life of Shambhavi Singh the artist unfold?

I live in an apartment whose little balcony I have filled up with my favourite plants. Waking up I tend to them, water them, nurture, nourish them. Then I go to my studio, a short distance, 5 minutes away. There I live through the day with my art. Nurture them and nourish them. Then in the evening I come home like the farmer. Nurture myself. Nourish my small family. Sum total of my day.

I go to sleep, early, at night.

Which national and/or international artists have influenced you the most?

Mark Rothko, Anselm Kiefer, Nasreen Mohamedi, Arpita Singh are the artists I really admire for their brevity, minimalism and the thoughts, political, subliminal that drive their work. However as an artist I think I have ploughed a ‘Lonely Furrow’. I have not really been ‘influenced’ in any particular way but would say that the larger art fraternity, in India and abroad, has constantly nourished me, helped me grow.

Any unfulfilled painting that you desire to paint and have not been able to do so?

I work therefore I am. All fulfilment comes through sitting, thinking, drawing, enacting. If something good comes out of it, it becomes my expression, my art. I just would like to keep my practice alive. Always. Forever. That is about all.