Art and Crime

Written by Monica Arora

“The criminal is the creative artist; the detective only the critic.” Thus spake British author G.K. Chesterton and while reading about the gruesome incidents pertaining to the murder of renowned artist Hema Upadhyay and her lawyer under mysterious circumstances, I was compelled to explore the relationship between artists and crime. As the case in question is concerned, Hema’s estranged husband, acclaimed artist Chintan Upadhyay was one of the accused. Respecting their space and privacy, and the fact that the case is sub-judice, perhaps it is best to let the law takes its own course.

Interesting to note here is how this artist couple, lovebirds entangled within the confines of conventional matrimonial ties were always poles apart, be it in their creative ouveurs or their social personalities. Whilst Hema continued to win accolades such as the coveted Triennale prize at the 10th International Triennale in New Delhi or her shows at celebrated international galleries namely the Grosvenor Vadehra in London, Bodhi Art in Singapore, Singapore Tyler Print Institute, MACRO in Rome, Studio la Citta in Verona, her sensitive portrayal emanating her struggle to “fit in” and her sensitive version of “feminity” rendered her a voice to be reckoned with.

Meanwhile, Chintan did collaborate with his much talented wife for certain shows and the couple’s middle name was controversy with them displaying a self portrait entangled in a passionate liplock for the brochure of a show or Chintan posing in the buff for another.

Being an avid reader and watcher of stylish crime thrillers be it through books or movies, one often wonders if the artist can be perceived as the superlative of all criminals with his or her inner angst and passion being reflected through their crime? Is their ultra sensitivity to the world around them a reflection of their capability to create art but if pushed beyond a limit, can it also leads to bouts of violent crime?

Strangely enough, world history has thrown up names of several prominent artists who have been linked to crime. Sample these: 17th century Roman artist Caraveggio easily tops this list as his art was a mirror to his aggressive personality transporting audiences to the mean streets of troubled and crime-prone Rome and his ultimate crime was committing murder which he expressed through a painting of the severed head of Goliath. Passion and fury at its peak!

Severance package … detail of David with the Head of Goliath by Caravaggio. Photograph: Archivo Iconografico/ Archivo Iconografico, S.A./CORBIS

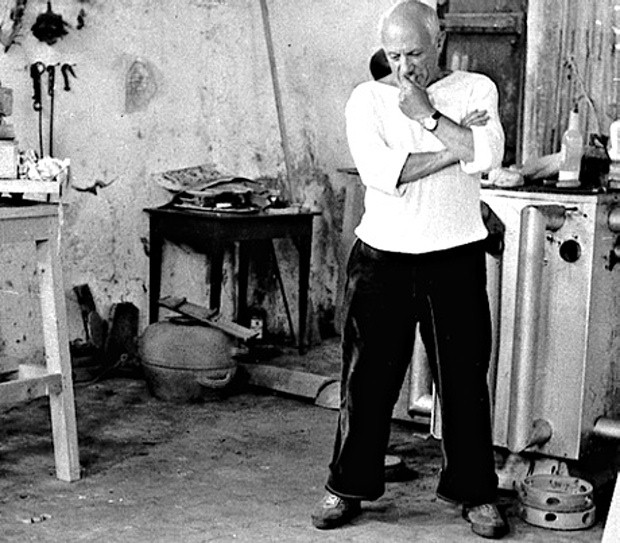

If Cellini was a ruthless murderer who killed merely for the sake of killing, there were also those artists whose crimes were of a less bloody nature…Picasso was accused of receiving a consignment of stolen sculptures from Louvre that he “studied” in his studio and was “inspired” therein to create his own masterpieces.

Of course theft of precious idols from temples and museums regularly make news in India, the most recent case being that of Subash Kapoor, a New York-based art dealer who, over a 30-year career, is alleged to have sold hundreds of stolen works worth more than $20m worth of stolen Indian antiquities. Art crime, perhaps, never goes out of fashion!

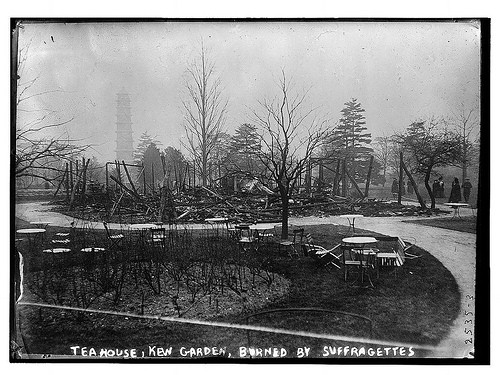

Way back in the early 20th-century, a contemporary of Picasso in Britain, Olive Wharry, a painter and suffragist, known for her serene watercolours was imprisoned for burning down the tea house at Kew Gardens. A real contrast of what appears to the eye and what brews within!

The Austrian artist Egon Sciele was actually accused of a crime more than a century ago of what is still viewed as a crime by certain schools of thought and societies: he had dared to paint models in their underwear in 1912, a horrific act of sexual perversion for the “conservative and conscious” people of those days. Strange isn’t it how nudity continues to be raked in controversy even in the contemporary times. Particularly in India, where censorship and intolerance have assumed outrageous proportions of violent acts, bans, blasphemies, fatwas and what not. Despite all the so-called modernization, mindsets are in actual regressive mode.

Taking the relation that exists between artists and crime, here one can delve into a recent exhibition held in 2015 entitled Forensics: The Anatomy of Crime, which featured Bosnian artist Sejla Kamerić’s, Ab Uno Disce Omne (From One, Learn All), whose earlier artworks attempted to analyse the war that eventually resulted in her father’s death created a monument of data as she states, “I found out how the information about what happened is becoming lost. Because of the political vacuum, even the scientific facts are being erased and the one thing which is very much needed is to have the collective narrative of what actually happened. The lack of, for example, a list of missing persons 20 years after the war is horrific, or the means of how to get the information on the location of mass graves or execution sites or concentration camps.” Interestingly, the curator Lucy Shanahan discovered that majority of the most eminent creations dealing with crime and its aftermath in the exhibition were by women artists.” She recalls an article about the forensic botanist Patricia Wiltshire: “She suggests women have a higher tolerance for gore. Maybe it’s oddly to do with the fact that we are thought to be more empathetic. She certainly observed that women tended to cope better in these situations.”

In another exhibition that she curated way back in 2006, the young Mexican artist Luis Miguel Suro, 18 months after the her friend’s murder, she lifted a section of the tiled floor taken from the studio where he was shot and killed in order to mark the episode. In the artist’s words, “The death of an artist, in their own environment, signified that violence was getting closer and closer to the educated, artistic community. Before that, it was assumed it was something that only happened to the poor, the violent, the ones involved in crime and drug dealing.”

It is interesting how a seemingly innocuous connect exists between art and crime. The thought of course seems rather improbable, almost far fetched if one takes into account how art, perceived as creative, aesthetic, and stimulating, almost meditative can be associated with gore, blood, violence and morbidity but yet, scratch the surface and one discovers how contemporary society and its raging issues of violence, mindless war, terrorism and intolerance has permeated the realms of the art world. Sad, yet so potent! As renowned British author Dorothy Leigh Sayers states, “The heavier the lashing of the rain and the ghastlier the details, the better the flavour seems to be.”